On August 25, 2018, I had the honor to participate the London First International Guqin Conference, located at SOAS University of London, organized by London Yolan Qin Society.

At 2:30pm I gave a talk. My talk was in session 2: Aesthetics and Iconography, after Mr. Luca Pisano (Associate Professor of Chinese Language and literature, Kore University of Enna, Italy) who presented "Preliminary Remarks on Qin Iconography from Chen Yang's 陳暘 Treatise on Music Iconography (Yuetulun 樂圖論)"

Chair was Mr. Edward Luper (Chinese art specialist at Bonhams auction house) who also gave a presentation in the morning session about The Qianlong 乾隆 Emperor's Guqin: Craftsmanship, Nostalgia and Virtue.

Here is my presentation and some of the slides that I have used, including those that I did not use (under dash lines) , due to limited presentation time.

My topic is A Philosopher’s Qin Sound. And the subtitle is Comparison of Two Qin Players Performances to Understand Their Interpretation.

The qin player, Xu Hong, who lived from the late 16th century to early 17th century, wrote a very important text about the aesthetic of Guqin, called Xi Shan's Epithets on Qin music. Xu Hong mentioned that he was constantly seeking three kinds of harmony. First, harmony between strings and fingers, then harmony between fingers and the sound, and finally harmony between the sound and the mind. He believed that once these three are in harmony, the highest degree of harmony is achieved.

Influenced by the idea of a “harmony between the sound and the mind”, I have analyzed the two masters: Yue Yin from last century in Beijing, and Zhuang Xi who passed away two years ago in Taiwan. I have used recordings of LZYF from each artist to help in my comparison.

Master Yue Ying and Master Zhuang Xi are two interesting candidates for this study. The reasons are : Their playing is considered quite moving. They have very different playing styles. They both are female qin players and specialized in Silk string. YY was The only female recording collected in *Lao Ba Zhang, The Old 8 Collections. Not many female philosopher qin players are well known, ZX was a philosopher qin player, she studied philosophy in college. They both *dapu and played the Daoist piece *Liezi Rides On The Wind 列子御風 *Dapu is the activity of teaching yourself a particular piece from the original notation without a teacher.

The categories of comparison that I am going to discuss today are :

A. Two Master’s Life backgrounds.

B. Their playing of Liezi Yufeng.

Now I will brief talk about their life backgrounds

Here are photos of Yue Ying from young to young adult to her mid age. From these photos, we can sort of see that Yue Ying was growing up in a traditional art atmosphere environment and living a rather wealthy life at that time.

Yue Ying was born in Beijing in 1904. She was the first daughter of Yue Jingyu 樂鏡宇 who was the owner of the oldest and now the largest Chinese pharmaceutical company 同仁堂. Yue Ying started learning the guqin at age 8 from Jia Kuo-feng 賈闊峰 (who was a businessman before he became a guqin teacher). Jia’s teacher was Huang Mian-zhi 黃勉之 (1853-1919). Huang was the most famous guqin teacher in Beijing during the late 19th to early 20th century. Yue Ying had her first public performance at age 13 in 1917. In 1962, she recorded Liezi Rides On The Wind at age 58.

Here are some Photos of ZHuang Xi. The 2nd one from the right was taken in 2013 when she performed the LZYF at Nantou Taiwan, when she was 64 years old, and that was the playing she decided to put into her solo album - The Crane Singing Collection 鶴鳴集.

Zhuang Xi was born in Shinchu Taiwan, majored in Philosophy in 輔仁 Catholic University. She studied guqin with Master Sun Yuqin when she was 23 years old in 1972. She established 天穆閣絲弦琴社 in 2003. She wrote several articles related to guqin and arts. In 1998, at the Guqin- Exploration of body and mind event, she mentioned that quote,

…我覺得我們應該走回歸的路, 回歸到內在精神的探求, 而不要迷失在音樂的唯美之中, 並不是說音樂的美不好, 而是說最好是在音樂真正的內涵中尋求進展...

“… I feel that we should seek inner spirits and not simply lose ourselves in the aesthetics of music. This does not mean that beautiful music is not good music, but that it is best to seek progress from the true inner meaning of music…”

-- Zhuang Xi

Recording Resources

錄音來源

Yue Ying’s LZYF is collected both in The Old 8 Collections 老八張 and Jue Xiang 絕響.

Zhuang Xi’s LZYF is from her solo album The Crane Singing Collection 鶴鳴集.

(I have more writing about these records below at the bottom two slides)

Now let’s look the piece LZYF.

From Ming to Qing Dynasties, there are 34 qin manuscripts carrying this piece. 神奇秘譜 (published in 1425) is the earliest surviving manuscript carrying LZYF. According to SQMP, it was composed by 毛敏仲 from Southern Song Dynasty, based on a daoist story from [Liezi] Huangdi (yellow emperor) chapter 列子黃帝. Master Yue Ying was using 研露樓琴譜 published in 1766 . Master Zhuang Xi was using 自遠堂琴譜 published in 1803 . 自遠堂琴譜 had a statement mentioning that 研露樓琴譜 was one of the Qinpu that 自遠堂 used for reference. These 10 titles from SQMP could help qin players to understand this piece better, although Yan pu and Zi pu do not have these titles. Now let’s see how different 列子御風 is in these two handbooks.

Here is a record of differences in each section in both handbooks. From my next slide, we can see some examples.

In general, LZYF in these two handbooks are about 80% the same with 20% differences. They both have 10 sections, and the construction of each section is the same. This is the first section of both handbooks and the red lines are the differences, such as Bo vs Tuo, Repeat from ] or repeat from the beginning, Duan Suo vs Xiao Suo, and where to do vibrato such as yin or nao, chuo, zhu, zhaung, do, huan, and the comma, period, and pause indication.

Regarding the Bo and Tuo, according to the fingering explanation of both handbooks, basically Bo in YYL and Tuo in ZYT means the same that they both are plucking the same direction with the right thumb. And it does not affect the sound pitch.

Here is a chart I list out the differences on hui positions indication by strings. For example, on the 5th string, one note YYL indicate on 6th hui while ZYT indicate on 6.3 hui. And the two players played differently as well. YY played on 5.8 while ZX did play on 6.3. The biggest difference between the players playing is a note on the 6th string that created a two and half step difference in pitch, while the handbooks indicated the same hui position.

Here is another difference of how many times the indication of “rapid” and “slow” shows in both handbooks. By checking the notation of “Rapid” and “Slow”, it might help us to sense the tempo of the piece. Section 6 has more rapid indication in Yanlu Lou qinpu than Zi Yuan Tang Qinpu.

Now we are going to hear some music.

Before I play some of the sound recordings, I would like to explain that with respect to the note and pitch analysis, I first had to lower the pitch of Yue Ying’s recording by 1.01 semitones without changing the tempo, in order to make the comparison easier. Yue Ying’s playing was pretty fast, I just have to assume that the recording of YY’s playing is accurate on tempo. This slide is to show pitches of the 1st and 2nd notes from the very beginning of both recording. On the left, I have two images together, the adjusted and the original recordings of YY. On the right is from ZX’s recording. Assuming A=440Hz, Yue Ying’s original tuning were closer and higher to B, at the 1st string, while Zhuang Xi’s tuning were closer and higher to Bb at the first string.

Here I marked up two phrases from the beginning of the first section of both players. The top one is from YY’s playing, the bottom one is from ZX’s playing. If we read the notes starting from the left, we can see that ZX played a longer opening note as if she had a “少息” noted there. And this is just her interpretation, it is not noted in the tablature. Now let’s see the blue arrow which is different between the two tablature, where the phrasing of the tablature is indicated with a period. If you look above, the blue arrow shows that YLL qinpu indicates that the opening phrase should be longer by three notes. However, both players interpreted different. ZX’s phrasing is as if she moved the period over to the second note next to it. And the blue underlines from YY’s part is that the tablature indicate to repeat from the angle mark while ZYT qinpu indicate repeat from the beginning. YY did play repeating from the angled mark and she played in different tempo within two times, while ZX totally omitted the repeating. Then we see a red note added on both recording, that is Li 6 to 2 and both player played li 7 to 2. And then YY’s recording sound like she did not play Lafu but a sliding on first string up to 7th hui then lift up her left hand. While ZX’s recording sound like her left middle on first string 7th hui was omitted and quickly did a stronger accent on the la and fu. Let’s listen. When we hear the recording, we will hear YY’s playing first, then follow by ZX’s recording.

This slide is to show one similar fingering which are those two red underlined notes, Duan Suo and Xiao Suo. Duan Suo is to repeat a note to create total 5 notes, while xiao Suo is to repeat a note to create a total 3 notes. One player followed exactly while the other altered. We will hear that Yue Yin played exactly 5 notes (which I marked 5 red Vertical bars), while ZX only played 2 notes, which is onenote less than the technique xhao suo suppose to create.

Here we will hear a recording from section 6. Yue Ying add an extra note to play together with tiao 5th as Cuo 撮 to make the sound bolder. At the bottom, ZX again, played slower and she changed one vibrato note, zhuang 撞 to a sliding note Zhu xia 注下 to simplified the sound. And the blue color is one specific fingering that suppose to create total 8 notes but YY played total 11 notes while ZX played 8 notes.

The previous slide shows the two handbooks indicate one same playing technique, but the players took liberties. This slide shows a phrase from section 9 where the handbooks differ, and the players also took liberties here which were respect to hui positions. The red circled notes shows the hui positions differ in the two handbooks. And the red numbers I marked are the hui positions the players played.

The next recording we are going to hear is from couple phrases of section 6. Yue Ying followed the handbooks she was using, excepting some sliding and vibratos. While ZX took her liberties by omitting 6 notes (which are those green colored ones) and adding one sliding and one plucking note. She also very her technique such as sliding down to the 8th instead of plucking that string on the 8th hui. And she seems to have more accented notes than Yue Ying.

After hearing some of the recording, here is a chart to show how many notes both players omitted or added. Obviously, Zhuang Xi omitted more notes than Yue Ying and also add more notes than Yue Yin.

However, even Zhuang plucking fewer notes, she still used more time than Yue Ying. This is a chart to show time used in seconds of each section of both players. The yellow color is Yue Ying’s playing, the blue color is Zhuang Xi’s playing. Yue Ying used total 7 minutes 14 seconds, while ZHuang Xi used total 9 minutes 24 seconds.

The red lines in this slide indicates the tempo. This is my best attempt to finding the tempos of each piece. YY has bigger range of tempo and it does show that she played faster on section 5 to section 7, while ZX’s tempo is more even.

Conclusion

The difference between each handbook that the two players were using, could make qin players play differently. But the major difference is still relying on the interpretation of the qin players.

Zhuang Xi simplified some of the fingerings to play fewer notes but add more vibrato to elongate the distance between notes to create more “yun” 韻. She used the ancient notation as a frame and developed her own new piece of Liezi Rides on The Wind based on that frame. That is well reflect to her talk in Guqin - Exploration of Body and Mind. She was seeking her ideal genuine ancient sound to match her mind.

Yue Ying, although not much information left for us to study, through her recording, one can still recognize that she was more discipline to the notation she was using and played with energetic, well-knit and firm sound.

As you know, the way that qin music is noted allows for a great deal of interpretation in tempo, timbre, dynamics and accent, however these two scholars went beyond the notation on the page and added some of their own notes and techniques based on the underlying tablature. Almost like a little bit of improvising.

Finally, Although they had very different playing styles, they both reached the highest degree of harmony between the sound and the mind.

------------------------------

Sides not have shown in the presentation

… 我們說左手韻, 右手聲, 當聲多韻少時, 它的表達是很直接的; 韻是在宋明之後, 明朝的琴譜中大量出現吟, 猱等類的指法, 但上海的林友仁先生寫了 一篇文章, 指出在歷史上是由聲多韻少, 演變到韻多, 並預期未來可能會是多聲多韻的時代. 但我覺得這種演變似乎並不是很好.我覺得我們應該走回歸的路, 回歸到內在精神的探求, 而不要迷失在音樂的唯美之中, 並不是說音樂的美不好, 而是說最好是在音樂真正的內涵中尋求進展...

“… We say that the left hand plays “yun,” while the right hand plays “sound”. When “sound” is more than “yun”, the expression is very straight. “Yun” developed more after in Song and Ming dynasties. A lot of yin and nao vibrato techniques showing more on the Ming dynasty qin books. A qin master in Shanghai once predicted that in the future, it’ll be more yun and more sound. But I do not think it is a good direction of progress. I feel that we should seek inner spirits and not simply lost in the aesthetics of music which does not mean that beautiful music is not a good music, but that it is best to seek progress from the true inner meaning of music…” -- Zhuang Xi

… 我的整個生活史中, 我大部分都是跟創作者在一起: 畫者, 文學作者, 思考者, 我們都認為我們是在藝術中完成自己的, 這是自己對自己的交代; 另一方面, 如果我們進行思考的話, 我們希望這思考是原創性的, 而不是沿襲既成的想法去思考人的心靈, 去觀察人的內涵, 所以,在我的彈琴生活裡, 有三件事是真正重要的 : 第一, 安靜的生活環境, 即平靜的心靈空間; 第二, 人的內在, 這是非常影響我的因素. ... 第三點重要的因素才是文化...

… My whole life is hanging out mostly with creative people: painters, literatures and thinkers. We all think that we are expressing and achieving ourselves through art. On the other hand, if we think, we hope it is genuine, instead of following the established ideas to think about human mind, and to observe the connotation of human. Therefore, there are three important parts in my life of playing the guqin: 1st, a quiet living environment, that is a peaceful mind. 2nd, the connotation of human, that influence me very much… and the last is culture….” -- Zhuang Xi

My Qin Plays My Heart

“...就我彈琴來講,困頓的時候比順暢的時候多。...到了中年,大概四十歲左右,我突然間很嚮往道──道的精神,所以我把老師東西通通丟掉了。因為老師是文人,而且是情韻很重的文人,他的東西對我當時的心境來說通通都是扞挌,好像完全不對勁了,所以我就把它丟了。”

"As far as my qin playing, difficult times were more than smooth times… in my 40’s, suddenly, I was longing for the Dao - daoist spirit, so I gave up all the ideas that I had learned from my teacher. Because my teacher was a literati and was a very sentimental literati, his ideas were in conflict with my state of mind then. Everything felt not right to me, so I put them away…”

“...因為道是極為內化的...”

“...because Dao is very internalized…”

“因為我們樂曲的結構,是根據內心語言呼吸的句法;我們不是根據旋律的構造。旋律的構造是很直線、很呆板的。這個內心語言的句法,一定心要很清才有。心很清,你就是『我琴彈我心』就得了。...”

“... Because qin music construction is based on our inner heart language phrase and breath, but not based on the construction of the melody. The construction of a melody is very straight and rigid. The heart must be very clean and clear, then there is the inner heart language phrase and breathing rhythm. If your heart is very clean and clear, then just play the qin by following your heart, that’s all.”

-- Zhuang Xi

Here are two paintings by Zhuang Xi and one painting of Zhuang Xi, by Mr. Ye Shiqiang who was an artist and a qin maker and a friend of Zhuang Xi. The two on the left are the paintings painted by Zhuang Xi. She did not have professional training in traditional painting. From her paintings, we can see the simplicity and elegant style. The abstract one on the right is called "A Small Image of Zhuang Xi" painted by Mr. Ye Shiqiang. Does that look like a crane? These three images are from the album Heming Ji. The Crane Singing Collection.

If you are interested in this piece by Yue Ying that I am analysing or any other pieces from her, you can see there are not many recordings as far as I know. This chart shows Yue Ying’s recording in both sets of albums. The original 1962 recording of Yue Ying’s LZYF by Shanghai China Record is collected both in The Old 8 Collections and Jue Xiang. Yue Ying recorded it when she was in the age of 58. Now there is a total 13 pieces of 8 melodies of Yue Ying’s qin playing recording published.

(the ? marks -- in Jue Xiang, there might be a mistake of copying the record pattern # down, two different pieces has the same number)

Here is the chart of ZX’s recordings collection in Heming Ji, The Crane Singing Collection. There are a total of 8 pieces in Heming Ji. LZYF is the most recent recording of the pieces on this album, and was recorded at the Yaji of the 1st Taiwan Contemporary Qin Making Exhibition at Nantou, Taiwan, when she was at the age of 64.

Other than the 8 pieces of sound recording in Heming Ji, people also can find 8 videos of Zhuang Xi’s qin playing including one talk on Youtube.

For the Duan suo, both handbooks indicate to repeat a note to create total 5 notes, however, ZYT was using Xiao Suo, which was not listed in its fingerings explanation. Judging by taking reference from other books, Xiaoxuo is same as Beisuo, which is repeating a note to create total 3 repeating notes.

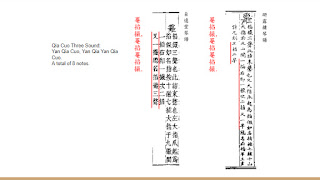

That is a fingering call Qia Cuo Three Sound. Here you can see the 2 handbooks the player

used, had the same explanation of the Qia Cuo Three Sound that it will create a total of

8 notes. (modified in 12/17/2018 that the Chinese character 掐 should be the correct character,

instead of 搯, based on that the 掐 character has been used since the earliest surviving

qin tablature, Yolan Wenzi Pu)

The Old 8 Collections which contains the LZYF piece by Yue Yin, is a set of guqin music recordings. It was recorded by China Record Shanghai Company and edited by China Art Research Academy . The full title is [An Anthology of Chinese Traditional and Folk Music - Traditional of Music Played on the Guqin]. It has collected 22 qin players performances with total 53 pieces and was primarily recorded in 1962 with a few recorded in 1956 and 1958. It was not published until 1992. Same recording can also be found in Jue Xiang, which was published last year in 2017.

For Zhuang Xi’s sound recordings, there is only one album, The Crane Singing Collection which contains only pieces performed by Zhuang Xi. This CD was published on Jan, 2016, three month before Master Zhuang passed away. LZYF was recorded when she was at the age of 64. According to one of the editors of the Heming Ji, Mr. Liu Xingyi, says that this piece had a harder time to work on, as the public yaji had a lot of background noise. They did a very good job to reduce the background noise and still maintain the sound of the playing as nature to its original sound as possible. This CD was published successfully thanks to her students’ hard working on design and editing by following Master Zhuang’s wishes. Fortunately she was able to see it and approve it.

Q&A

After the talk, in Q&A, Mr. Omid Burgin asked two questions: what software I was using and why use 44 for the time signature? My answer was: Reaper and MuseScore, and using 44 is due to my limited western music knowledge so I decided to use the basic time signatures just to help a little bit of the comparison, although it is not the best way to show.

Mr Marnix Wells pointed out the three four notes on ZX's part which I did notice while I was working on transferring ZX's music from reaper to MuseScore. In order to make two comparison less complicated, I decided still make ZX's part to 44 instead of 34.I want to thank Omid's suggestion of a free program to use for analysis music: https://www.sonicvisualiser.org/videos.html

Many Thanks to

要謝謝很多朋友: 包括, Marilyn Gleysteen, Juni L Yeung, Jiawei Mao, Lu Dan, 林嶽, 行一, 以及回我email 的幾位朋友. 要講謝辭, 才發現名單其實越來越多, 還包括現場技術幫忙的兩位年輕人, Dennis and Max? not sure their names. And president Cheng Yu, secretary Julian Joseph, Charles Tsua from LYQS. 最大的感謝是 my beloved husband.